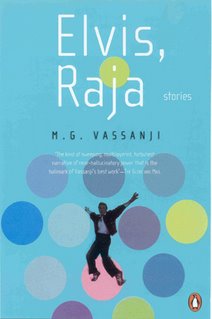

Elvis, Raja

M G Vassanji

Penguin

Pages: 218; Price: Rs 250

Rootlessness is also a problem with the second-generation American and British Indians, too. And all these children who may or may not have missed the

Vassanji, who is the author of five critically-acclaimed novels in the past and who is a name to reckon with among Canadian-Indian writers today, has penned twelve stories of migration, traumas, bitterness and hope (or is it hopelessness?). True, Vassanji has style — and in some stories substance — and his craft is thousand times better than the sob stories written by behanjis sitting in high-rise apartments of

Vassanji has got the drift right, and he does not try to bring in all the clichéd problems of the irritating Indians living abroad — like their love for pickles and agarbatti. Instead, he tries to focus on the extraordinary, vividly portraying his characters’ diverse dilemmas, sans losing grip of the Indian identity.

So far so fine. But the problem with this book is it has nothing new to say. Just another one dozen short stories. Maybe the exceptions, though not really, are the title story and When She Was Queen. In Elvis, Raja Rusty worships Elvis so crazily that he creates a shrine to the legendary singer. Diamond, his college chum, traumatised because of his unfaithful wife’s deeds, finds himself trapped in Rusty’s and the Pop King’s world of trance.

When She Was Queen gives an excellent peep into the lives of the Indian community living in

The tales range from Gujarat to

— Sunil K Poolani / Deccan Herald